Are you a runner thinking about intermittent fasting? If so, we have put together this runner’s guide to intermittent fasting to help you decide if this style of eating is right for you.

In this article, we will cover specific types of intermittent fasting, the pros, and cons of intermittent fasting, and the research behind whether or not intermittent fasting works.

Our goal is to give you all the information you need to know, so should you decide to try it, you can apply it without compromising your running performance.

Note: We are not here is promote any style of eating, but rather to share our experience and research so you can decide for yourself if intermittent fasting is right for you.

Intermittent fasting has been shown to be clinically safe for healthy adults. However, seek out the advice of your doctor or a registered dietitian if you have underlying health conditions before starting a fasting regimen.

- What is intermittent fasting?

- Most common intermittent fasting schedules

- Which intermittent fasting schedule is best?

- Who should avoid intermittent fasting?

- What happens to your body when you fast?

- What are the benefits of intermittent fasting?

- What are the disadvantages of intermittent fasting

- Is intermittent fasting better than traditional dieting?

- Fasted running vs intermittent fasting

- Other research references

What is intermittent fasting?

Intermittent fasting (IF) is an eating style that is based on when you eat versus what you eat. The basic idea behind intermittent fasting is to cycle long periods of fasting with shorter periods of eating. Over time this can lead to lots of benefits for runners.

When done properly, intermittent fasting is a great way to help you lose weight, burn fat, and reduce the risk of certain diseases like Type II Diabetes.

Fasting can help regulate appetite-related hormones (such as leptin, ghrelin) as well as increase the production of growth hormones which may help runners with muscle repair and healing. Increased focus, mental clarity, and improved sleep are also common.

Intermittent fasting has been shown to reduce insulin dependency one of the primary indicators of early metabolic disease.

We will get more into the benefits of intermittent fasting as we go through this article.

Is intermittent fasting a diet?

While many agree, intermittent fasting is not a diet, healthy food choices are an important part of intermittent fasting.

So whether or not that is enough to call intermittent fasting a diet, we won’t argue it either way.

If your definition of diet is based on reducing calorie intake, then yes, intermittent fasting can be a form of dieting since most people tend to eat less when intermittent fasting. But intermittent fasting isn’t just for weight loss. People adopt intermittent fasting for many reasons.

Where did the idea of intermittent fasting come from?

According to Mark Mattson, Ph.D., a neuroscientist at John Hopkins, our bodies are designed to go long periods of time without eating. Over thousands of years, our ancestors had to hunt for food.

Since hunting for food often took long periods of time lots of energy was expended. Going without food could last for hours, even days. This cycle of fast/feast was frequently repeated and was the way of life for early humans.

Even as late as the 1950s or 1960’s, most fasted. We just didn’t call it that.

Adults and children typically ate three meals per day and rarely snacked between meals. If dinner was at 6 pm, most would not eat again until breakfast unless it was a special occasion. Breakfast got its name from “breaking the fast”.

Nowadays, due to the easy availability of food, especially snacks and low nutrient-density food, many of us eat throughout the whole day. We grab snacks in between meals and we often grab snacks in the evening as we sit down to watch TV or read a book. As a society, many of us tend to stress-eat due to our busy lives. Emotional and social eating also contributes to how often we eat.

What happens when we eat too frequently?

Frequent eating patterns mean our glucose levels and insulin remains spiked all day.

When unchecked, this can lead to overeating and increased fat storage. Glucose and insulin play an important role in how hungry we feel (by triggering the increase or decrease of hunger hormones), as well as how we use food for energy, or store excess calories.

Excessive fat stores, especially around our midsection, and unregulated insulin/cortisol levels make us at a higher risk for weight gain, metabolic disease, and other health conditions.

Why would someone choose intermittent fasting over a low-calorie diet?

If you are trying to lose weight or burn fat, you need to slightly reduce caloric intake.

Intermittent fasting, when done properly enables calorie restriction as well as a host of other benefits that traditional low-calorie diets don’t do.

When we choose intermittent fasting as a style of eating, we are reducing the time we eat to a smaller period of the day.

Because our eating window is reduced, it helps us maintain focus to eat healthy during our eating window. As a result, we tend to consume less food.

As our fasting period approaches and goes above 16 hours, we also see a decrease in the production of hunger hormones so that when we enter the eating period, we may not be as hungry.

Later in the fasting period, fat burning increases once our body has switched from using glucose and glycogen (a stored form of glucose) as a primary energy source over to fat.

Intermittent fasting is not a magic bullet

We have to be smart about how we apply intermittent fasting. It doesn’t work for everyone.

If weight loss is your primary reason for intermittent fasting, you have to be careful. You can still overeat by overcompensating especially if you try to cram all the missed snacks you normally would have eaten inside the eating window.

However, many people claim it feels easier than traditional low-calorie restrictive diets because hunger is curbed and restricted to smaller periods of the day when hunger hormones have peaked. Those who have tried traditional dieting have reported that they have more frequent bouts of hunger because the hunger hormones never reach a point where they get suppressed.

As you will see later in this article, there are pros and cons of intermittent fasting, and there is more to intermittent fasting than just fat loss.

Most common intermittent fasting schedules

The most common types of intermittent fasting are carried out either in short eating windows on an everyday basis or by choosing a certain number of days to fast during the week followed by non-fasting days.

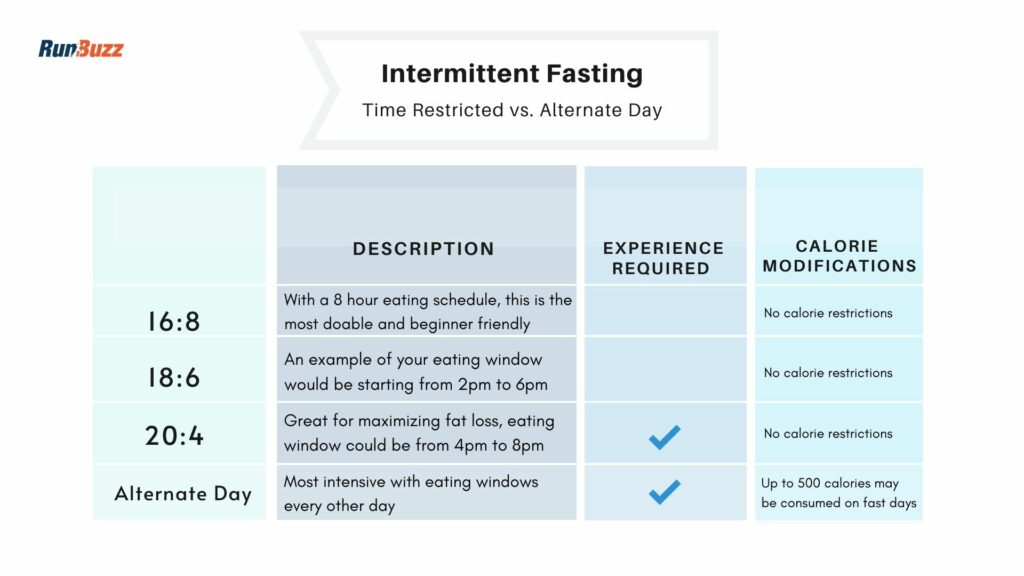

Time-restricted fasting, the most common type of intermittent fasting, is fasting every day over a specified time window. For example, you may fast over a 16, 18, or 20 hour period, and then eat during the remaining hours of the day.

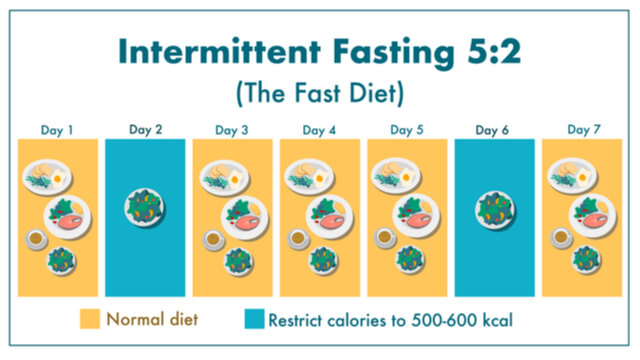

Whole-day fasting, also known as the 5:2 diet, focuses on fasting two non-consecutive days each week while the other days are free to eat without restrictions.

Alternate Day fasting as the name suggests is alternating between fasted and non-fasted days every 24 hours.

Long-term fasting (sometimes known as prolonged or extended fasting) is the most extreme form of fasting which can go 2-30 days without eating. This form of fasting is generally not recommended for runners. However, on occasion or as part of religious practices prolonged fasting can be done.

Let’s get into more specifics.

Time-restricted eating (TRE)

Time-restricted fasting is reducing the feeding window to a certain period and typically this range is 4-10 hours.

According to this study in Current Atherosclerosis Reports on time-restricted eating stated the following:

“Human trial findings show that time-restricted eating(TRE) reduced body weight by 1–4% after 1–16 weeks in individuals with obesity, relative to controls with no meal timing restrictions. This weight loss results from unintentional reductions in energy intake (~350–500 kcal/day) that occurs when participants confine their eating windows to 4–10 h/day. TRE is also effective in lowering fat mass, blood pressure, triglyceride levels, and markers of oxidative stress, versus controls. This fasting regimen is safe and produces few adverse events.”

Below are the most common fasting intervals depending on your goals and experience.

16:8 fasting

A 16:8 intermittent fasting schedule is the most common time-restricted eating pattern and it is one of the best ways to start intermittent fasting.

The “16:8” refers to an 8 hour period of eating with a 16-hour fast. During this time, only water or non-caloric beverages can be consumed.

During the 16-hour fast time, it is important to eat healthily. The longer the eating period, the more likely you are to overeat. An example of a 16:8 hour fast might be to wake up, have a late morning brunch, and eat dinner normally.

18:6 fasting

The 18:6 intermittent fasting schedule has a slightly longer period of fasting with a shorter eating period of only 6 hours. For example, your eating cycle may be from 12-6 pm or 2 pm to 8 pm. For most, this may mean eating two meals a day (lunch and dinner) and skipping breakfast altogether.

20:4 fasting

The 20:4 intermittent fasting schedule is often referred to as the “the warrior diet”. The warrior diet was part of a health program created by Ori Hofmekler and is 20 hours of fasting combined with a 4-hour window of eating. An example eating schedule would be having your first meal at 2 pm and wrapping up dinner by 6 pm.

One meal a day (OMAD)

For this type of intermittent fasting, you eat one meal every 24 hours. This type of fasting generally is for rapid weight loss and generally is not recommended for runners due to the likelihood of too much caloric restriction.

Alternate day fasting or 5:2

The 5:2 intermittent fasting protocol (sometimes known as The Fast Diet) is comprised of two days of fasting with 5 days of eating normally. It requires more intensity because it has you fasting every other day.

Alternate day fasting is considered to be one of the most intensive. But fasting days can be modified to eat up to 25% of daily caloric needs or 500 calories on your fasting days.

Alternate day fasting can help with the overall caloric deficit of as much as 37% demonstrated by the following review of several studies.

This review looked at 11 meta-analyses from 130 clinical trials on four types of intermittent fasting. Studies found reliable evidence that the 5:2 or alternate day fasts with zero-calorie alternate-day fasting led to a greater fat reduction in overweight or obese adults.

Long term fasting

Usually, these fasts are done a minimum of 36 hours and can extend up to 30 days (2-5 day fasts are the most common type of extended fasts) and allow consumption of water, tea, electrolytes, and non-caloric drinks.

Which intermittent fasting schedule is best?

For beginners, we recommend starting out with a 16:8 or 18:6 fasting interval. These fasting schedules are the easiest and most sustainable, especially until you get used to what fasting feels like.

While tempting, a highly restricted fasting schedule such as 20:4, or one meal a day (OMAD) fasts are tough at first. For most, these require strict concentration and mental preparation. When done correctly, longer fasts have the most dramatic impact on fat burning if weight loss is your primary goal as well as the increase in human growth hormone production and autophagy which we will cover later in this article.

The nice thing about intermittent fasting is that you can control what fasting schedule you would like, or even mix it up and build a fasting schedule that works best for you.

The best intermittent fasting schedule is the one you can keep without disrupting your life.

Who should avoid intermittent fasting?

Fasting is not for everyone. Intermittent fasting has been clinically shown to be safe for most healthy adults. However, before starting an intermittent fasting protocol, you should discuss it with your doctor or registered dietitian. Some health conditions can be dangerous when mixed with fasting.

Children and adolescents under the age of 18, seniors, and individuals with a history of disordered eating, should not intermittent fast. Women who are trying to conceive, are pregnant, or have had interrupted menstruation during fasting should stop immediately or be sure to clear it with their doctor.

Those with underlying conditions such as diabetes, kidney disease, and heart disease should also avoid intermittent fasting until they have discussed it with their doctor.

What happens to your body when you fast?

So what actually happens in our body when you stop eating for long periods of time?

In this section, we dig into the metabolic phases your body undergoes when fasting.

There are five phases known as zones that our body enters depending on our time in a fasted state.

- Anabolic zone

- Catabolic zone

- Fat-Burning zone

- Ketosis zone

- Deep (long-term) ketosis zone

The exact time you enter each of these fasting zones depends on individual genetics, what you eat during your eating period as well as your daily activity level.

Therefore the following estimated time ranges can differ from person to person.

Anabolic zone (0-4 hours after eating)

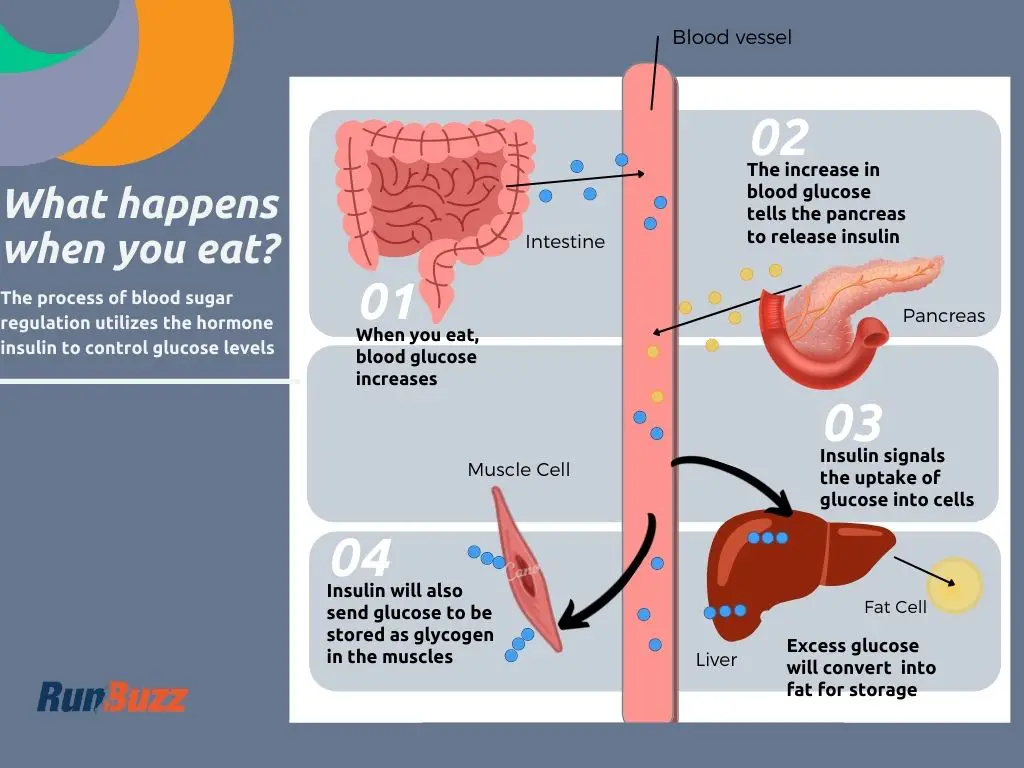

Once you have eaten your last meal, your body goes to work breaking down food into glucose, amino acids, and fatty acids. Carbohydrates are converted into glucose, protein into amino acids, and fats into fatty acids.

Glucose is released into the bloodstream. Glucose levels in our blood tell the pancreas it’s time to produce insulin.

The pancreas responds to this influx of glucose by releasing insulin. Insulin helps get important nutrients like glucose, amino acids, and fatty acids into our cells to produce muscle, fat, and glycogen. Insulin resistance is a term to describe the cell’s resistance to receiving these important nutrients and is a bad thing.

Leptin increases. Leptin is referred to as the satiety hormone. Leptin acts as a regulator of weight management and energy balance. Leptin also interacts with the hypothalamus in our brain to control metabolic homeostasis throughout our central nervous system. During this phase it communicates with the hypothalamus to tell our body we aren’t hungry. After all, we just ate.

Ghrelin decreases. One of the things Ghrelin is known for is the stimulation of hunger. This hormone is released by several organs but mostly from the stomach. As time goes by, Ghrelin signals the hypothalamus to initiate hunger. During the first few hours after eating, the production of Ghrelin decreases, so we no longer feel hungry.

So that intense feeling of hunger you get when you are hungry? Yeah, that’s ghrelin working at what it does best. Ghrelin also contributes to the release of human growth hormones and is involved in other body functions. This release of growth hormones which help build muscle and can help with tissue repair accelerates even more in later stages of fasting.

Glucagon is released by cells in the pancreas. If blood sugar levels are low, glucagon is released from our pancreas to tell the liver to break down glycogen and release it as glucose into the blood. Glucagon serves as the pathway to stimulate gluconeogenesis.

Gluconeogenesis is the process of making glucose (sugar) from the breakdown of lipids (fats) or proteins.

Catabolic zone (4-16 hours after eating)

In the next phase of fasting, the catabolic zone, blood glucose drops as your body is now using it as your primary source of energy.

The pancreas has increased glucagon production and this triggers liver glycogen breakdown. Glycogen is the stored form of glucose and is used as the next best source of energy once glucose levels have dropped. Glycogen (and later fat burning), will break down and create glucose so your blood sugar stays regulated.

Note for runners: Glycogen replenishment during eating periods and after runs is important for runners who want to perform their best. Yes, you can run almost indefinitely on fat stores once glycogen has been depleted, but you won’t perform as well during high-intensity or high-performance running without it. Later in this article, we will discuss how you can time your runs better with your eating periods to maximize performance while intermittent fasting.

Another thing that happens during the catabolic phase is that the body prepares itself for autophagy that starts in the next phase pf fasting. Autophagy is a cellular repair process that is best described as the body’s ability to clean up old, damaged, or dead cells.

Towards the end of the catabolic zone, the first ketones start to be produced. Ketones are an energy source that feeds muscles and organs such as the brain, during fasting. When fatty acids from gluconeogenesis are released, the liver can convert them into ketone bodies.

Accelerated fat burning zone (16 hours after eating)

This is where things get interesting and the benefits of intermittent fasting start to accelerate.

Our body is always burning fat. But until it has used up most of our glucose in our blood and stored glycogen in our liver, body fat is not the primary source of energy. Carbohydrates (aka sugars) are.

During this phase, lipolysis starts to break down fat stores into energy. (eg. we start to burn more fat than sugars from the foods we eat.) It’s the process ( gluconeogenesis) that releases fatty acids and glycerol into the blood. This step allows fat cells in the adipose tissue to be freely used to create sugar in the blood.

Gluconeogenesis replenishes glucose in the blood using triglycerides that were formerly in the adipose (fat) tissue and released as glycerol and fatty acids. The simplified version is, when you enter the fat-burning zone, your energy source normally taken from glycogen is not available. So your body actually comes up with this cool process of gluconeogenesis to create a primary source of energy from fatty cells in the adipose tissue. Pretty cool right?

Autophagy begins. At this point, a really exciting process called autophagy begins. Autophagy helps with cellular repair and cleans out dead or damaged cells that aren’t working properly. Some claim that autophagy may even reduce the risk of Alzheimer’s, although more research in this area is needed.

Ketosis zone (24-72 hours after eating)

After 24-72 hours, full-blown fasted ketosis has started. At this point, ketones are our primary source of energy. The process of ketogenesis is in full swing converting fatty acids into ketones. Liver glycogen is considerably low and has stopped being the main source of energy. Our liver and pancreas gets some rest.

Ghrelin, our hunger generating hormone has decreased. Every 24 hours Ghrelin levels fall so by day 3, you’re looking at very low output. This explains why the longer you fast, the less you feel hungry. Our body is happy using fat stores for energy.

Autophagy continues to increase and be more effective. Many who enter ketosis whether it be from longer fasts or the Keto diet report inflammation is drastically reduced. Autophagy is one of the reasons why along with additional human growth hormone output that facilitates repair.

Deep ketosis zone (3+ days after eating)

In the deep ketosis zone or the prolonged fasting phase, your body is in a steady state of ketosis where glucose and insulin remain at stable levels and our appetite remains low. Ketones continue to be produced from the breakdown of fatty tissue. This continues to fuel our muscles and our brain.

Insulin has been reduced by 30% or more which has been shown to reduce metabolic disease. An increase in growth hormone and a decrease in insulin resistance have been linked to several positive health benefits like the reduction of inflammation and improvements in overall metabolic health.

Reaching this phase has been shown to offer many benefits including increasing cells’ resistance to toxins. Many report mental clarity and increased focus during this stage as well.

Autophagy is maximized and cellular repair accelerates to its highest level of effectiveness.

What are the benefits of intermittent fasting?

Intermittent fasting as you have probably deducted can counter excess fat storage. It does this by regulating insulin levels and helping the body to efficiently utilize fat cells for energy. This process can help us increase our metabolic rate as long as we eat sufficient calories during our eating period.

According to Dr. Eric Berg, a chiropractor, and expert in intermittent fasting and weight loss, benefits go beyond just weight loss. Other benefits include reducing or stabilizing inflammatory conditions like arthritis and tendonitis as well as effects on cognitive function and improved mental clarity.

Since high insulin levels hahave been linked to high blood pressure, intermittent fasting can help reduce those high insulin spikes from frequent eating which helps regulate blood pressure.

In the following video, Dr. Berg walks through 23 Benefits of Intermittent Fasting. In this particular video, he focuses on the One Meal A Day (OMAD) fasting schedule, there is a nice review of overall fasting benefits.

Intermittent fasting can improve metabolic syndrome because it combats insulin resistance.

Intermittent fasting has been shown to be an effective prevention and treatment protocol for type 2 diabetes as shown in the following review of several studies on intermittent fasting and the treatment of Diabetes:

“The majority of the available research demonstrates that intermittent fasting is effective at reducing body weight, decreasing fasting glucose, decreasing fasting insulin, reducing insulin resistance, decreasing levels of leptin, and increasing levels of adiponectin. Some studies found that patients were able to reverse their need for insulin therapy during therapeutic intermittent fasting protocols with supervision by their physician. (Albosta, M., Bakke, J. Intermittent fasting: is there a role in the treatment of diabetes? A review of the literature and guide for primary care physicians. Clin Diabetes Endocrinol 7, 3 (2021).)

What are the disadvantages of intermittent fasting

Fasting can make you feel unpleasant, especially as your body gets used to fasting protocols. Hunger due to the early release of appetite hormone ghrelin can make you really feel hungry. This hunger peaks for a few hours but then mostly goes away. One way to combat this is to stay busy during these periods and you won’t notice them as much.

Another disadvantage of intermittent fasting is that it can lead to binging or over-eating as well as under-eating during your eating periods if you aren’t careful.

If someone has a history of eating disorders or tendency to disordered eating, there could be a risk that fasting could lead to new or reoccurring eating disorders. If this is you, it is probably best to skip intermittent fasting and seek out a dietitian to discuss options.

Fasting can lead to poor athletic and running performance when increased speed or intensity is desired in your training regimen.

Running in a fasted state, can increase the state of stress being placed upon your body. This increases the production of stress hormones (mainly cortisol) which stimulates fat storing, especially if you eat immediately after a fasted run. We will discuss this one later in this article when we talk about how to run and do intermittent fasting in a way that supports your running.

Since our cortisol is elevated due to exercise, reintroducing food after a fasted run increases our glucose levels, and supercharges our body to put it into fat-storing mode. So while we may burn more fats during our run, we have a higher risk of replacing even more fat after the run. For those who intermittent fast to lose weight, this is what we are trying to avoid by being fasted in the first place!

Is intermittent fasting better than traditional dieting?

No intermittent fasting is just a different style of eating and we tend to eat less (just like traditional diets). However, intermittent fasting does have additional benefits over traditional diets in other areas.

According to an article published in the Integrative Medicine Alert. Jun2020, Vol. 23 Issue 6, p1-5. 5p:

• Intermittent fasting led to similar weight loss as continuous energy restriction in several human trials when compared head-to-head.

• Sustainability of intermittent fasting was similar to continuous energy restriction, but not superior.

• Other markers, such as insulin resistance and fat mass, improved more with intermittent fasting than continuous energy restriction in preliminary studies but more research in this area could clarify whether added benefits exist with intermittent fasting.

Fasted running vs intermittent fasting

Fasted running is running during a period, or near the end of a fasting period before you have eaten. Like getting up in the morning to go for a run before breakfast). It is about the ‘timing’ of when you run.

Intermittent fasting is a repeated cycle of eating/fasting periods and is more of a style of eating. Depending on when you run, it could be a fasted run. But intermittent fasting is a style of eating.

Fasted running can be bad idea depending on your reason for running fasted

You may have heard of runners who swear by running in a fasted state. You may even be one of those runners. The argument for running in a fasted state is that you have less glucose and glygogen available so your body has to turn to fat burning as a source of energy. And that is true. But it is not the whole story.

Is it OK to run in a fasted state?

The short answer is yes. Running in a fasted state is safe.

If you run at an easy, low intensity pace then running in a fasted state is fine and you probably won’t notice any side effects. However if you regularly run fasted, especially on long runs or high intensity runs, things start to change.

“When we run, our bodies release cortosol. Cortisol is a stress hormone that gets released whenever we are under physical or mental stress. Excessive cortisol can be detrimental and has been linked to weight gain and obesity.

Our bodies, release cortisol when we exercise, but especially during periods of high intensity exercise or long bouts of endurance exercise. When combined with food after a run, it can actually trigger metabolic changes that cue the body to take higher percentages of the food you ate and store more of it away as body fat to compensate for the high level of stress. Cortisol is a strong anti-inflammatory hormone that is tied to high intensity exercise (or from our flight and fight instincts that get triggered when our body is under stress)

But wait, doesn’t running reduce stress?

Yes, generally speaking.

When we run, we release endorphins to help counteract stress. Exercise leads to lower cortisol levels several hours later and during periods of sleep. So exercise is a good thing and we shouldn’t worry about cortisol during exercise unless we are worried about how it may specifically impact our ability to increase overall fat loss.

Should I skip breakfast before a run?

If you are someone who likes to go run before eating breakfast, you will be fine as long as your runs are short and relatively low intensity.

However, fasted long runs or hard intensity exercise (like a hard Tempo runs or track intervals) can lead to an increase in hunger throughout the day, overeating, and cortisol induced fat storage. This is why a lot of endurance athletes like half and full marathoners gain weight during the training cycle. Yes you may burn more fat for energy while on the run, but you risk eating more and what you do eat stores more away as body fat to help your body have those fat reserves it neds for those future long runs.

Running fasted often offsets the goals you intended to have in the first place with fasted running

A better approach to running while fasting (e.g intermittent fasting)

So if fasted running can increase our fat storage and make us hungry, how can we run and intermittent fast at the same time?

It’s easy. If weight/fat loss is your primary reason for fasting, don’t run high intensity runs during or at the end of a fasting period.

Instead, run an hour or two after you have eaten, or within a few hours of your last meal in the early anabolic stage of fasting. This allows your body to pull fuel from blood glucose and glycogen stores so that it uses up a lot of the glucose that would be influenced by elevated cortisol levels and have glucose and glycogen available for that higher intensity exercise. Fat to energy utilization is slow, but glycogen and glucose can be tapped for energy almost immediately.

If you are fasting for reasons other than fat loss, then you can run any time. It won’t matter, but you will have more energy if you run a couple hours after you have eaten something.

If you run at the beginning of the fasting period (an hour or two after your last meal), you will ultimately store less fat and reduce your glycogen levels faster, which will help get you into the accelerated fat burning stages sooner.

Other research references

Albosta, M., & Bakke, J. (2021). Intermittent fasting: is there a role in the treatment of diabetes? A review of the literature and guide for primary care physicians. Clinical Diabetes and Endocrinology, 7(3). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40842-020-00116-1

Brashich, A. D. (2021, May 24). The Different Types of Intermittent Fasting. Healthcentral.com. https://www.healthcentral.com/condition/intermittent-fasting-types

Colorado State University. (2019). Glucagon. Colostate.edu. http://www.vivo.colostate.edu/hbooks/pathphys/endocrine/pancreas/glucagon.html

Combs, D. (2021, May 7). Metabolic Step-By-Step: Stages of Fasting In The First 72hrs – Temper. Temper. https://usetemper.com/learn/metabolic-step-by-step/

Dhillon, K. K., & Sonu Gupta. (2019, April 21). Biochemistry, Ketogenesis. Nih.gov; StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK493179/

Endocrine Society. (2022, January 23). Endocrine-related Organs and Hormones. Endocrine.org; Endocrine Society. https://www.endocrine.org/patient-engagement/endocrine-library/hormones-and-endocrine-function/endocrine-related-organs-and-hormones%C2%A0

Espelund, U., Hansen, T. K., Højlund, K., Beck-Nielsen, H., Clausen, J. T., Hansen, B. S., Ørskov, H., Jørgensen, J. O. L., & Frystyk, J. (2005). Fasting Unmasks a Strong Inverse Association between Ghrelin and Cortisol in Serum: Studies in Obese and Normal-Weight Subjects. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 90(2), 741–746. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2004-0604

Folsom, A. R., Eckfeldt, J. H., Weitzman, S., Ma, J., Chambless, L. E., Barnes, R. W., Cram, K. B., & Hutchinson, R. G. (1994). Relation of carotid artery wall thickness to diabetes mellitus, fasting glucose and insulin, body size, and physical activity. Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study Investigators. Stroke, 25(1), 66–73. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.str.25.1.66

Gunnars, K. (2016, August 16). 10 Evidence-Based Health Benefits of Intermittent Fasting. Healthline. https://www.healthline.com/nutrition/10-health-benefits-of-intermittent-fasting#TOC_TITLE_HDR_3

Gunnars, K. (2020, April 21). Intermittent Fasting 101 — The Ultimate Beginner’s Guide. Healthline. https://www.healthline.com/nutrition/intermittent-fasting-guide#who-shouldnt

Izumida, Y., Yahagi, N., Takeuchi, Y., Nishi, M., Shikama, A., Takarada, A., Masuda, Y., Kubota, M., Matsuzaka, T., Nakagawa, Y., Iizuka, Y., Itaka, K., Kataoka, K., Shioda, S., Niijima, A., Yamada, T., Katagiri, H., Nagai, R., Yamada, N., & Kadowaki, T. (2013). Glycogen shortage during fasting triggers liver–brain–adipose neurocircuitry to facilitate fat utilization. Nature Communications, 4(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms3316

Kubala, J. (2018, July 3). The Warrior Diet: Review and Beginner’s Guide. Healthline; Healthline Media. https://www.healthline.com/nutrition/warrior-diet-guide

Mendoza-Herrera, K., Florio, A. A., Moore, M., Marrero, A., Tamez, M., Bhupathiraju, S. N., & Mattei, J. (2021). The Leptin System and Diet: A Mini Review of the Current Evidence. Frontiers in Endocrinology, 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2021.749050

myDr. (2018, August 26). Pancreas and insulin: An Overview. MyDr.com.au. https://www.mydr.com.au/pancreas-and-insulin/

NIH. (2019, March 26). Diabetes, Heart Disease, and Stroke | NIDDK. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/diabetes/overview/preventing-problems/heart-disease-stroke

Southern California Hospital Culver City. (2021, July 13). Managing Your Weight with Intermittent Fasting and Time Restricted Eating | Southern California Hospital at Culver City. Www.sch-Culvercity.com. https://www.sch-culvercity.com/news/2021/managing-your-weight-with-intermittent-fasting-and-time-restricted-eating/

Stanton, B. (2021, January 10). Extended Fasting: Benefits, Tips, and How To Get Started. KETO-MOJO. https://keto-mojo.com/article/extended-fasting-benefits/

Stekovic, S., Hofer, S. J., Tripolt, N., Aon, M. A., Royer, P., Pein, L., Stadler, J. T., Pendl, T., Prietl, B., Url, J., Schroeder, S., Tadic, J., Eisenberg, T., Magnes, C., Stumpe, M., Zuegner, E., Bordag, N., Riedl, R., Schmidt, A., & Kolesnik, E. (2019). Alternate Day Fasting Improves Physiological and Molecular Markers of Aging in Healthy, Non-obese Humans. Cell Metabolism, 30(3), 462-476.e5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2019.07.016

The Physiology of Fasting. (2019, September 29). Zero; Big Sky Health. https://www.zerofasting.com/the-physiology-of-fasting/

Tipane, J. (2021, April 14). High Intensity Interval Training and Cortisol: Is HIIT Backfiring? Healthline. https://www.healthline.com/health/fitness/the-cortisol-creep#What-is-cortisol

Torres, L. (2021, June 15). 7 safety tips for practicing extended fasting – LIFE Apps | LIVE and LEARN. LIFE Apps | LIVE and LEARN. https://lifeapps.io/fasting/7-safety-tips-for-practicing-extended-fasting/

University of Southampton. (n.d.). How the body produces glucose when we are fasting. FutureLearn. https://www.futurelearn.com/info/courses/understanding-insulin/0/steps/22456

Wisner, W. (2022, January 18). Is intermittent fasting safe? The Checkup. https://www.singlecare.com/blog/is-intermittent-fasting-safe/

You and Your Hormones. (2018). Ghrelin | You and Your Hormones from the Society for Endocrinology. Yourhormones.info. https://www.yourhormones.info/hormones/ghrelin/

- About the Author

- Latest Posts

Steve Carmichael is a running coach, sports performance coach, nutrition coach and has been a recreational runner for over 18 years. Steve holds multiple certifications as a certified running coach through the RRCA and USA Track and Field as well as he is a NASM certified personal trainer, and PN1-L1 certified nutrition coach.

Steve has been coaching since 2010 and has helped thousands of runners online and in the Central Ohio area maximize performance and run injury-free.

Steve is the founder of RunBuzz and Run For Performance.com. If you are interested in working with Steve though his online running and strength coaching services, feel free to reach out.